Living on empty…

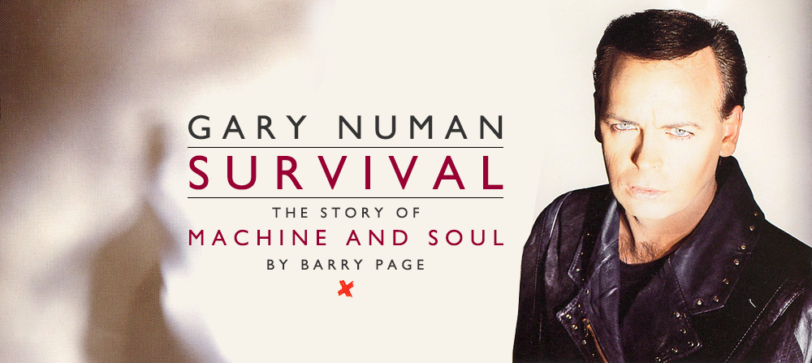

In 1992, prior to his impressive career renaissance, Gary Numan hit funk rock bottom with Machine and Soul, an album which its maker later labelled as ‘the worst thing I’ve ever done’. Barry Page tells the story of the synth-pop pioneer’s annus horribilis.

![]()

In September 2017, Gary Numan’s Savage (Songs from a Broken World) (see TEC review) went straight in at number 2 in the UK chart, his first studio album to hit the Top 10 since 1981’s Dance. Indeed, by the time of this remarkable career turnaround, it had been many years since the Hammersmith-born musician’s commercial peak in the late 70s and early 80s; a period which saw the release of huge hit singles such as ‘Are “Friends” Electric?’, ‘Cars’ and ‘We Are Glass’, as well as the albums, Replicas, The Pleasure Principle and Telekon, which are now widely acknowledged as electronic classics of the time.

In the years that followed, Numan squandered much of his early windfall – said to be £6 million – on flashy sports cars and aeroplanes, as well as extravagant stage sets and lighting that lost him money on every tour. On top of this, there were some disastrous career moves, like the extraordinary decision to retire from touring at the peak of his success.

By the time of the formation of Numa, the singer’s own record label – arguably, the ultimate pop star indulgence – both his profile and commercial appeal had significantly waned, a problem that was compounded by a well-publicised refusal by Radio One to play any of his new music. However, that’s not to say that there weren’t any more hit singles, and, in 1986, there were back-to-back Top 40 entries with ‘This is Love’ and ‘I Can’t Stop’. But, while Numan was still more than capable of crafting a hit, his frustration over his faltering career was palpable, as evidenced by the lyrics to cuts such as 1988’s ‘New Anger’ (‘I’ve read the papers / Look at this / They say that I’m all over’).

OUTLAND

By 1991, the hits had dried up, and Numan was now releasing records on IRS (International Record Syndicate), an American label, whose roster had once included R.E.M. and the Go-Go’s. The label had been co-founded by Miles Copeland III, one-time manager of the Police and brother of drummer Stewart Copeland. Such were the label’s generous advances, the singer was prepared to put up with the control freakery of Copeland, who convinced him that he still had commercial pulling power, both in the UK and overseas. There was the insistence on petty lyric changes, the truncation of album titles (Cold Metal Rhythm became Metal Rhythm) and, in the case of the US release of that particular album, there was not only a different title – New Anger – but a head-scratching running order that included tracks from 1984’s Berserker.

It was also Copeland who advised Numan that he should try recording some cover versions, but his initial choices – the much-covered ‘Sixteen Tons’ and the Box Tops’ Billboard chart-topper, ‘The Letter’ – were bizarre, to say the least. Numan was savvy enough not to play ball on this occasion, but he did compromise with two Prince covers (‘U Got the Look’ and ‘1999’), particularly since the diminutive hitmaker’s music was becoming increasingly influential in his own recordings. Toeing the corporate line with Copeland was something Numan would later regret, as he explained to The Arts Shelf in 2012: “What I should have said, was, ‘Bollocks, I’m not fucking doing that and I’m not doing that either, and you can stick your promotional budget up your arse’. That’s what I’d have said in ‘79 and that’s what I’d say now. But my career was in trouble, I was running out of money, I had all kinds of debts, and he seemed like a lifeline. More than that he seemed like he might open up America again and so I sold my soul.”

Numan’s stint on IRS saw the release of two studio albums – Metal Rhythm and Outland – and a live collection, titled The Skin Mechanic, but none of these releases were commercially successful. Neither was Automatic, the moonlighting musician’s collaboration with Shakatak’s Bill Sharpe – released on the Polydor label in 1989 – which failed to build upon the Top 40 successes of the singles, ‘Change Your Mind’ and ‘No More Lies’.

Eventually, IRS pulled the plug on their reported million-pound record deal, and Numan was, not for the first time, placed in a precarious financial position. “The bank threatened to repossess my house, so we put it up for sale,” he recalled in his 2020 autobiography, (R)evolution. “At one point, we even discussed adapting my mum and dad’s garage and moving in there. The only thing that saved the house was that no one came close to offering enough money for it.”

However, the reported £500,000 debt was just the beginning of a nightmare period for the singer, one which would see both the collapse of his long-term relationship with his girlfriend, and the release of an album that he would all but disown shortly after its release.

THIS ISN’T MUSIC, THIS IS SURVIVAL

Following his release from IRS, Team Numan rallied. At this point in his career, Numan was still being managed by his father, Tony, while his mother, Beryl, was still running the fan club. His girlfriend, Tracey Adam, meanwhile, was also playing a key role. Adam had already had a hand in the artwork for Outland, and her graphic design skills would be called upon over the next few years, as would her burgeoning skills as both a music video director and cost-cutter.

With no new record deal in sight, Numan reactivated his Numa label, which had laid dormant since 1986’s charity single, ‘I Still Remember’, and got back to work in his recently rewired Outland studio. A single, ‘Emotion’, a derivative slab of funk that took its musical cue from David Bowie’s ‘Fame’, was swiftly released in September 1991, but it failed to chart. The release coincided with an 18-date tour of the UK (plus one show in Brussels). With its smaller club-sized venues and scaled down production, costs were minimised, while the introduction of some fan club telephone lines – which offered news, competitions and works-in-progress of new songs – helped to top up the coffers.

On paper, everything was in place as Numan entered a new, more frugal era. Following the Emotion tour, the musician continued to work on a new album, one he anticipated would alleviate some of his money worries. However, the pressure he put on himself to create anything of worth would prove detrimental to the sessions, as he explained in (R)evolution: “I was so desperate for every song, every note, to be special, I would listen back at the end of each day and erase everything I’d done. Nothing seemed good enough, and day by day my confidence crumbled a little more. To begin with, I was writing furiously, coming up with a torrent of ideas, but none that I thought were as good as they could be. That pace slowed to a crawl, and each day became a demoralising disappointment. I went for months and didn’t keep a single thing, not one second of recorded music.”

It seems absurd now that Numan was suffering from writer’s block, particularly given the fact that the singer had, just 12 months before, been on somewhat fertile creative ground, not just with the Outland album – which was a vast improvement on 1988’s Metal Rhythm – but also the soundtrack work (with stalwart Mike Smith) for Rodman Flender’s horror movie, The Unborn. Weirdly, it was this soundtrack work that would ultimately signpost Numan’s future, and many of the sound vignettes – that included a strong use of choral effects, courtesy of the musician’s Korg M1 workstation – were recycled on albums and B-sides. Despite the fact that many of the ephemeral pieces weren’t used in the film, Numan was proud of the music and disappointed that IRS had no interest in putting out a soundtrack album. (Human, co-credited to Michael R. Smith, was belatedly released on the Numa label in 1995.)

For Machine and Soul, Numan would abandon the more experimental aspect of his music, convincing himself that a contemporary rock/funk sound – that took in elements of Bowie, Prince and Michael Jackson – was his ticket back to the all-important Top 40. “I really am interested in rock music, and I like the idea of things that are funky,” he told Future Music in 1992. “If you can take that funk feel, something that’s real groovy and danceable, then put heavy-duty guitars over the top with interesting vocal arrangements and work hard on the other sounds that are there – good snare and bass sounds, for instance – then you’re starting to get something that’s quite exciting.”

ISOLATE

Although Numan was struggling to finish his new album, he was at least able to release a brand new single, ‘The Skin Game’, in March 1992. Typical of much of his output from this period, the track was swamped with wailing female vocals – this time, courtesy of former Shakatak member, Jackie Rawe – but there was at least a powerful chorus rising above the parapet of its cluttered grooves. Its interesting patchwork of lyrics, meanwhile, offered a further insight into the author’s troubled state of mind; in particular, his disillusionment with the media (‘You’re welcome to fame / You’re welcome to try / I’ve been on TV, sold my face to you’).

The single, which peaked at a disappointing No.68, coincided with the release of the Isolate album, a hotchpotch collection of full-length versions of tracks released on the Numa label between 1984 and 1991, featuring genuine gems such as ‘My Breathing’ and ‘My Dying Machine’, alongside more pedestrian white funk (see ‘Emotion’ and ‘Your Fascination’). Both the album and its accompanying 13-date UK tour proved to be a welcome distraction for the struggling musician, as he told the fan club that year: “The tour was outrageous. I’ve never laughed so much in my life. Kipper and Susie Webb joined the band and turned each day into a comedy. Kipper proved himself to be one of the best guitar players around and added an energy and excitement to the on stage performance that I had wanted from the band for a long time.”

It was Numan’s guitarist Keith Beauvais who had introduced the singer to Kipper (aka Mark Eldridge), the lead vocalist and guitarist for One Nation, who’d released an album, Strong Enough, on IRS in 1989. During the Isolate tour, Numan had confided in him about his problems with the album, and the charismatic guitarist offered his help. “He took four songs away to his home studio,” Numan recalled in 1997’s ghostwritten autobiography, Praying to the Aliens, “and I went round to his house one night with [my girlfriend] to listen to what he’d done. He played his new versions and they were considerably more musical than my own efforts. I realised that it wasn’t the way I should be going but, to be honest, I didn’t really have a choice. What else could I do?”

Some of Kipper’s contributions to Machine and Soul were later criticised by fans for being self-indulgent, as evidenced by the overblown funk of ‘Generator’ and its grating false ending, but, in truth, the album’s biggest problem was that the new songs simply weren’t good enough, and the inclusion of his stale run-through of Prince’s ‘U Got the Look’ reeked of desperation. However, that’s not to say that the album – which peaked at a lowly No.42 – wasn’t without its high points. Both ‘The Skin Game’ and the bawdy title track were serviceable enough pop singles, and then there were the two ballads, which had both started out as soundtrack ideas for The Unborn. Firstly, there was the tender ‘Love Isolation’ – something of a forerunner to 1994’s ‘You Walk in my Soul’ – and ‘I Wonder’, an outstanding track that just about got away with its heavy-handed percussion. Overall, though, Machine and Soul was the sound of a musician on autopilot. “I tried and tried to convince myself that it was the right album, but I knew it wasn’t,” Numan admitted in (R)evolution. “It was all I had, so I released the worst album I’ve ever made when I needed to have made the best. I don’t think I have ever felt more ashamed and hopeless. The sleeve was shit as well. I hadn’t just lost my way musically – I’d lost it in every way. I was the lowest I’d ever been.”

I’LL GIVE YOU CORROSION

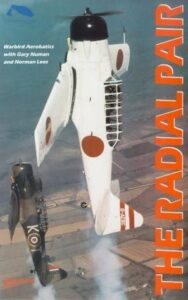

Despite Numan’s musical woes, there had been some high points in 1992. The musician’s passion for aviation has, of course, been well documented, and that particular year he’d teamed up with fellow pilot, Norman Lees, to form the Radial Pair, who performed audacious aerobatics in vintage aeroplanes on the air display circuit. Tracey Adam, who was officially still Numan’s girlfriend at the time, had directed a video featuring interviews with the daring duo, plus footage of their various stunts. Later, Numan tasked himself with creating a soundtrack for the eventual VHS video release and, in doing so, set the template for his next album, which would see him abandoning the funky guitars, saxophones and session singers that had been watering his sound down since 1985’s The Fury, in favour of a more robust and industrial sound. The first fruits of these recordings were aired during his upcoming tour, with each show opening with the instrumental, ‘Mission’.

Despite Numan’s musical woes, there had been some high points in 1992. The musician’s passion for aviation has, of course, been well documented, and that particular year he’d teamed up with fellow pilot, Norman Lees, to form the Radial Pair, who performed audacious aerobatics in vintage aeroplanes on the air display circuit. Tracey Adam, who was officially still Numan’s girlfriend at the time, had directed a video featuring interviews with the daring duo, plus footage of their various stunts. Later, Numan tasked himself with creating a soundtrack for the eventual VHS video release and, in doing so, set the template for his next album, which would see him abandoning the funky guitars, saxophones and session singers that had been watering his sound down since 1985’s The Fury, in favour of a more robust and industrial sound. The first fruits of these recordings were aired during his upcoming tour, with each show opening with the instrumental, ‘Mission’.

Crucially, following the end of his relationship with Tracey Adam in 1993, Numan began dating a fan named Gemma O’Neill, who would play a pivotal role in his career renaissance over the next few decades. “She walked into this person that was absolutely broke, whose career was completely at a standstill, in a terrible state, virtually no money coming in,” Numan told Ultimate Classic Rock in 2018. “I had no record contract, it looked very unlikely that I’d ever get one, tours were still losing money, and the attendance was becoming embarrassing.”

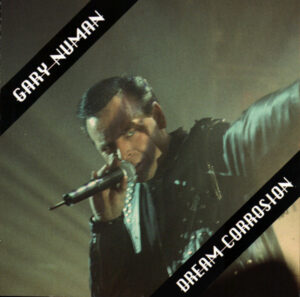

O’Neill suggested that Numan should reconnect with his ailing fan base by integrating older songs into his live sets. The result was the well-received Dream Corrosion tour, which also included a support slot on Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s Liberator tour at the end of the year. On the final date of the tour, there was a sentimental return to Wembley Arena, the scene of Numan’s ill-fated retirement in April 1981. OMD had, of course, once supported the musician during their years as a fledgling synth-pop duo with a tape recorder (Winston), but Numan was unconcerned by this veritable reversal of fortunes and leapt at the opportunity to play to bigger crowds.

Although there would be no new music released in 1993, fans were offered the opportunity to purchase a new version of Machine and Soul, which included extended version of the songs (the divisive ‘Generator’ was stretched to almost ten minutes!). During the same year, the Beggars Banquet label began a reissue programme, which included a new compilation of Numan’s earlier material – not dissimilar to 1987’s Exhibition – and four double CDs, which included a studio album on each disc, plus various bonus tracks. Numan’s stock hadn’t been as high for years, and it paved the way for an exciting new era, one that would begin with the career-invigorating Sacrifice album (see TEC feature previously) the following year. “I feel as though I’ve suddenly remembered how I used to think, how to do what I used to do best,” he told the fan club. “This time I’ve shut myself away, with virtually no outside help or input, and wrote and played almost everything on my own. For good or for bad, this will be the most Numan of Gary Numan albums for many, many years.”

Gary Numan’s latest album, Intruder, is released on 21 May.

- QUEEN’S MACHINES – How Music Changes Through The Years (1979 – 1984) - July 25, 2021

- SUGAR RUSH – The Story of ‘Sugar Tax’ - May 7, 2021

- Survival – The Story Of ‘Machine and Soul’ - April 30, 2021