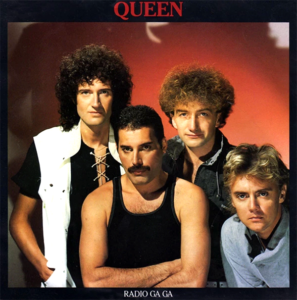

Following the relative failure of their disco-infused Hot Space album, Queen bounced back with ‘Radio Ga Ga’, a bona fide synth-pop classic. Barry Page looks at the legendary rock band’s use of synthesisers, which culminated in the making of this iconic track.

![]()

“I was highly amused about ‘Radio Ga Ga’, because Queen always made a point of saying ‘no synthesisers were used’, and then the best song they ever write was all synthesisers!” – Andy McCluskey, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark

Released in January 1984, Queen’s first single in nearly eighteen months saw the legendary rock band return with a fresh and contemporary electronic sound – replete with robotic vocals and synthetic drums – that would attract a new audience of admirers. Over a decade on from their chart debut, it saw the quartet continuing their love affair with electronics, one that had begun, somewhat tentatively, with the June 1980 release of their transatlantic number one album, The Game, which was recorded at Euro disco pioneer Giorgio Moroder’s Musicland Studio, with its in-house engineer and producer Reinhold Mack at the helm. (Mack’s working relationship with Queen would endure through to A Kind Of Magic in 1986.) It’s been well documented that Queen had previously eschewed such technology, even going to the lengths of declaring ‘No synthesisers!’ (or similar) on the credits of a string of hit albums in the 1970s, but, with a new decade just around the corner, the band were seemingly keen to move with the times. “We wanted people to know that all those guitar and vocal harmony things weren’t synthesisers,” guitarist Brian May explained to Sounds magazine in 1983, referring to those oft-quoted tags. “In the end, when synthesisers grew up and we grew up, we decided there’s no reason to be that fussy about it – as long as they don’t replace us.”

May had been quietly impressed by Stevie Wonder’s groundbreaking use of the Moog on classic albums such as Fulfillingness’ First Finale and Innervisions, but it was drummer Roger Taylor who had first brought a synthesiser to his bandmates’ attention during the recording of The Game. Created by Oberheim Electronics, the sturdy OB-X synthesiser had first been unveiled at a US trade show – organised by the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM) – in the summer of 1979, and was developed in response to the launch of Sequential’s fully programmable Prophet-5 the previous year. “I had an engineer working for me called Jim Cooper and we put our heads together and said we better do something,” the pioneering manufacturer’s founder, Tom Oberheim, explained to MusicRadar in 2019. “Between November 1978 and June 1979 we developed the OB-X, a project that would normally take a year but took us six or seven months. When I went to the NAMM show in the summer of 1979, I got to Atlanta wondering if by the end of the show I’d still be in business because the Prophet-5 was smoking in those days, but by the end I’d written about half a million dollars of business for the OB-X in around three days.”

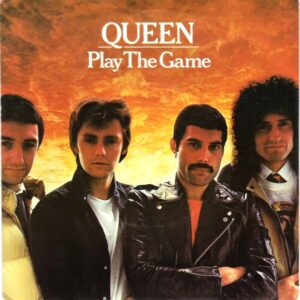

Oberheim had previously introduced the OB-1, the first ever totally programmable synthesiser in 1978, but it was its polyphonic successor, the OB-X (and the subsequent OB-Xa), that would find favour with an array of synth-pop acts throughout the ensuing decade, including Eurythmics, Japan, New Order, Gary Numan, OMD, Simple Minds, Talk Talk and Ultravox. Though other acts, such as the Police, Rush and Van Halen (see ‘Jump’) would also use the instrument, Queen were one of the first rock bands to seize upon its sonic possibilities. May’s gentle embellishment of the ballads ‘Sail Away Sweet Sister’ and ‘Save Me’ confirmed an initially cautious approach to the new technology, but singer Freddie Mercury’s zeal for the band’s new toy was evident from the off, utilising it somewhat heavy-handedly on ‘Play the Game’, not just in the intro, but its near-comical trade-offs with May’s Red Special in the instrumental bridge. As Taylor confirmed to Mojo magazine in 2019, synthesisers “changed the way we did things”.

FLASH GORDON APPROACHING

For Queen’s next project – the recording of which was fitted in around the band’s final recording sessions for The Game and its ensuing tour – the band’s members experimented with the OB-X to a far greater extent on the soundtrack of Flash Gordon, the ambitious Mike Hodges-directed sci-fi movie which has become something of a cult favourite since its release in December 1980. “We wanted to experiment with all that new studio equipment,” recalled bassist John Deacon in the band’s official 1992 biography, As it Began. “We had always been keen to try out anything new or different whilst recording. The synthesisers then were so good, they were very advanced compared to the early Moogs, which did little more than make a series of weird noises. The ones we were using could duplicate all sorts of sounds and instruments – you could get a whole orchestra out of them at the touch of a button. Amazing.”

Despite the harsh time constraints placed upon them, the band were able to sonically match the broad colour palettes of the movie’s vibrant sets, creating a series of themes and sound vignettes that perfectly complemented the visuals. Additionally, the groundbreaking interpolation of selected film dialogue, at May’s insistence, ensured it was a soundtrack like no other. “We saw twenty minutes of the finished film and thought it very good and over the top,” he told the band’s official website years later. “We wanted to do something that was a real soundtrack. It’s a first in many ways, because a rock group has not done this type of thing before, or else it’s been toned down and they’ve been asked to write mushy background music. Whereas we were given the licence to do what we liked, as long as it complemented the picture.”

Explaining the songwriting process, May told Rocks Off! magazine: “After the first week – you know, almost everything came from that magical first week when we put all kinds of things down – we discovered we already had a lot of music that could be lined up with various characters and scenes. But, for instance, we didn’t really have a Ming the Merciless theme which worked, so at that point Fred said, ‘Okay, I’ll write the Ming theme’. And he went home and came back the next day with the Ming theme.” Whilst co-producer May was the undoubted driving force behind the project, his bandmates certainly rose to the challenge of creating music well outside of their comfort zone. Mercury’s playful ‘Football Fight’ and ‘Vultan’s Theme’ conveyed a sense of fun that matched the camp drama of the movie, while Taylor’s exploration of the synthesiser’s darker and more ethereal qualities – notably, on ‘In the Space Capsule (The Love Theme)’ – was vital, too, and something that would point towards his future solo work.

The Flash Gordon soundtrack has the sad distinction of having been released on the day of John Lennon’s senseless murder on 8 December 1980, but the single – May’s theme for the titular hero – and the album were both hits, unlike the movie itself, which was both a critical and box office flop at the time. Queen’s inaugural foray into the soundtrack world, however, went down well with reviewers. Sounds magazine described the album as “something extraordinary”, while Record Mirror wrote: “This is the sort of stuff I haven’t heard since Charlton Heston won the chariot race in Ben Hur. An album of truly epic proportions that warrants an equally epic five out of five.”

HOT SPACE, LET’S GO

Following the release of Flash Gordon, Roger Taylor played on a handful of tracks on Dance, the third solo album by Queen fan Gary Numan, then regarded as the music world’s first bona fide synthesiser star, following the No.1 single successes of ‘Are “Friends” Electric’ and ‘Cars’ in 1979. Taylor also experimented with some synths of his own – this time in collaboration with future Queen producer David Richards – on his debut album, 1981’s Fun in Space, cheekily emphasising the point with ‘P.P.S. 157 synthesisers’ in the record’s credits. Taylor’s penchant for new technology would extend to live arenas, too. Between 1978 and 1984 he incorporated Pollard Syndrums (first used on 1978’s Jazz album) and Simmons drum pads into his drum kit setups. “I very much enjoy playing with all the new toys that are coming out,” he explained to Modern Drummer magazine in 1984. “I’m certainly more up to date with all the new gadgets out on the market than I ever was a few years ago. I’m also a lot more open minded about them. For instance, when electronic drums first came out, I didn’t really like them very much because I never liked the sound of the bass drum, but I’ve found that the Linn Drum is much better in this department, and I enjoy using it.”

Queen’s next album would see the band continuing to experiment with synths, but, buoyed by the unexpected success of the Chic-inspired ‘Another One Bites the Dust’ single (particularly in the US), Soul and R&B fan Deacon would also succeed in encouraging his bandmates to take their music in a more disco-oriented direction, despite the fact that the genre wasn’t exactly in vogue at the time (a huge backlash had culminated in a mass burning of disco records in July 1979). Certainly, it had become evident that Queen were now pulling in different musical directions, and the Andy Warhol-influenced cover design of their upcoming new record would reflect the fact that there was a lack of unity within the band, a problem that would endure as the decade wore on. “We’re not so much a group anymore,” Deacon explained to Martin Townsend in 1985. “We’re four individuals that work together as Queen.” The bassist’s vision for the new album would also result in a number of fresh arguments. This was perhaps best exemplified by his clash with May over a guitar solo on ‘Back Chat’. “There wasn’t going to be a guitar solo,” May told Guitar Magazine in 1983, “because John, who wrote the song, has gone perhaps more violently black than the rest of us. We had lots of arguments about it, and what he was heading for in his tracks was a totally non-compromise situation, doing black stuff as R&B artists would do it with no concessions to our methods at all, and I was trying to edge him back toward the central path and get a bit of heaviness into it, and a bit of the anger of rock music.” In the end, May would get his own way, but Deacon would later have his revenge (of sorts), employing a session player to play the synth break on 1984’s ‘I Want to Break Free’ when a guitar solo seemed a more logical and aurally-pleasing option.

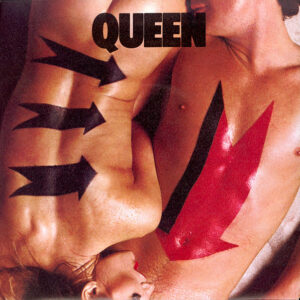

While Queen were applauded for their experimental approach on the excellent Flash Gordon soundtrack, their proliferating use of synths (which now included a Roland Jupiter-8) and synthetic percussion – notably, Simmons drum pads and a Linn LM-1 drum machine – didn’t go down so well, particularly with a fair chunk of their fans, who felt that the band were straying too far from their hard rock roots. (Mercifully, the coinciding tour saw the band playing more guitar-based, audience-friendly versions of the new songs.) However, that’s not to say there was a lack of quality on Hot Space, with highlights including the hit singles ‘Under Pressure’ (the band’s No.1 hit collaboration with David Bowie, released shortly after their best-selling Greatest Hits album in October 1981) and the sorely underrated, synth-infused ballad, ‘Las Palabras de Amor (The Words of Love)’. But, there were other tracks that proved to be less accessible. Alongside serviceable rock tracks such as ‘Put Out the Fire’ and the somewhat leaden ‘Dancer’, there were more divisive cuts such as ‘Cool Cat’ – which even Bowie, ostensibly, didn’t want to be associated with, removing his backing vocals at the eleventh hour – and ‘Body Language’, a surprise Billboard hit that was borne out of the band’s debauched Bavarian lifestyle. “Munich had a huge effect on our lives,” May recalled in 1992’s As it Began. “Because we spent so much time there, it became almost another home, and a place in which we lived different lives. It was different from being on tour, where there would be an intense contact with a city for a couple of days, and then we would move on. In Munich we all became embroiled in the lives of the local people. We found ourselves inhabiting the same clubs for most of the night, most nights! The Sugar Shack in particular held a fascination for us. It was a rock disco with an amazing sound system, and the fact that some of our records didn’t sound very good in there made us change our whole perspective on our mixes and our music. ” Built around a slinky, synth-based groove, ‘Body Language’ was perhaps more in keeping with Mercury’s later solo work, and the repetition of the slight, lascivious lyrics were a world away from the sinuous prog rock of 1974’s ‘The March of the Black Queen’. “The single and the video weren’t quite to my tastes,” Taylor admitted to Mojo magazine in 2019. “This was Freddie exploring the music of the gay clubs, which was fine. But also one of the rare occasions when I think he was a little selfish with the video. The rest of us were pushed into the background.”

Intriguingly, the weekly music press – who were renowned for lambasting Queen and their music – were unusually enthused by the band’s change of musical direction. In Sounds magazine, they wrote: “Queen have never made particularly blinding albums, but you’ll have to agree that Hot Space shows more restraint and imagination than tripe like Jazz”. New Musical Express also agreed, stating: “The production of the whole album is really a peach”. However, years later, in 2004, Q magazine placed it at No.5 on a list of albums ‘where great rock acts lost the plot’ (top spot went to Their Satanic Majesties Request by the Rolling Stones). May has since defended the album. “I make no apologies for the Hot Space album now,” he told the same monthly magazine the following year. “It took me a while to get into that philosophy of sparseness but it was very good for us, it was a good discipline and it got us out of a rut and into a new place.”

GAP YEAR

Later claiming that they were starting to get on each others’ nerves after twelve years of gigging and recording, the band decided to take a break once the Hot Space tour had wrapped in Tokorozawa, Japan, on 3 November 1982. As Deacon later admitted to Martin Townsend in 1985, the ensuing gap year was frustrating: “Working together as Queen is now actually taking up less and less of our time. I mean basically I went spare, really, because we were doing so little. I got really bored and I actually got quite depressed because we had so much time on our hands.” Certainly, the shy bassist was largely inactive, spending the majority of his spare time with his wife Veronica – who’d inspired the lyrics of 1976’s ‘You’re My Best Friend’ – and their expanding family (his fourth child, Joshua, was born on 13 December 1983). He did, however, co-write, play on and produce a long-forgotten rap single, ‘Picking Up Sounds’, credited to Man Friday and Jive Junior. And, like his fellow bandmates, he would play on Taylor’s second solo album, Strange Frontier, which would be released the following summer.

May was far busier, not only co-producing the debut album, Lettin Loose, by Heavy Pettin – viewed as Scotland’s answer to Def Leppard – but also taking a rare foray into session work, playing guitar on soul singer Jeffrey Osborne’s sophomore album, Stay With Me Tonight, including the title track which was later a Top 20 hit in the UK. Additionally, whilst in Los Angeles in April 1983, the moonlighting guitarist assembled a number of musician friends for the Star Fleet Project mini-album; namely, guitarist Eddie Van Halen – who’d played the memorable solo on Michael Jackson’s ‘Beat It’ single – plus session bassist Phil Chen (who would later guest on Taylor’s Happiness? album), REO Speedwagon drummer Alan Gratzer and keyboardist Fred Mandel, who’d not only played on and co-written Alice Cooper’s Roy Thomas Baker-produced Flush the Fashion album, but had also played keyboards on the North American and Japanese legs of the Hot Space tour. “I realised a big gap in my life was not playing with other musicians,” May told Sounds magazine that year. “I wanted to get out and find out what it was like to play with other people – I had almost never done it. We’ve never been into the superstar thing of people guesting on the albums. In this case we really needed it because we got sorely fed up with each other after we finished touring in Japan last November. We decided we couldn’t stand the sight of each other for a few months and we had to take a break. We needed new energy.” This energy was certainly evident on the rousing title cut (featuring Taylor on backing vocals), a faithful take on the Paul Bliss-penned theme to Star Fleet, a TV series that his young son, James, had introduced him to. (Originally broadcast in 1982, Star Fleet was essentially a dubbed version of a Japanese sci-fi series named X-Bomber, which employed Gerry Anderson-esque puppetry techniques.)

Meanwhile, Mercury had begun preliminary work on his debut solo album, which included some tracks with Queen fan Michael Jackson, a confirmed admirer of the Hot Space album, who had previously encouraged the band to release ‘Another One Bites the Dust’ as a single, despite Taylor’s well documented reservations. In the home studio of Jackson’s pre-Neverland mansion in Encino, the pair worked on three songs, which included early versions of ‘State of Shock’ and a sensitive ballad of Mercury’s titled ‘There Must Be More to Life Than This’, which dated back to the Hot Space sessions. Although there were rumours of a falling out due to Mercury’s alleged drug usage at the time, the fact that Jackson’s popularity had soared in the wake of the chart-topping ‘Billie Jean’ single ¬and its parent album, Thriller, ensured it was virtually impossible for the pair to complete the recordings. Mercury’s ballad was eventually reworked for 1985’s Mr. Bad Guy album, while ‘State of Shock’ became a minor hit for the Jacksons in the summer of 1984, but with the Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger replicating the ‘Killer Queen’ writer’s vocal parts.

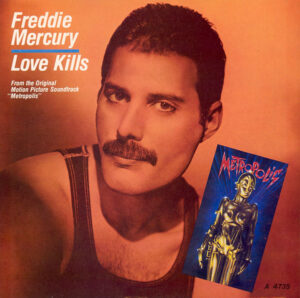

Additionally, Mercury worked on another extracurricular project with Eurodisco doyen Giorgio Moroder at Musicland Studios (according to Moroder, the precise date of their first meeting was 18 January 1983). At the time, Moroder was two years into his time-consuming Metropolis project. Having already sourced a high-quality print of Fritz Lang’s groundbreaking dystopian movie from 1927, the Italian maverick was now working on a contemporary soundtrack to accompany the movie’s re-release, which would include 80s heavyweights such as Adam Ant, Pat Benatar and Bonnie Tyler. Moroder and Mercury worked on an early version of ‘Love Kills’, but the pair didn’t always see eye to eye. “Freddie was a little difficult,” Moroder told Malcolm Gerrie in 2014. “He was not an easy guy to work with… He knew exactly what he wanted and there was a little bit of a conflict. I wanted it slightly different – he won!”

IT’S JUST A LIVING PASTIME

Whilst ‘Love Kills’ had originally been earmarked by Moroder for the Metropolis soundtrack, it also became a genuine contender for Queen’s next studio album. “Freddie wrote a track that was sent to us by Giorgio Moroder,” May confirmed to Classic Rock magazine in 2014. “To be honest, Freddie got rid of what was already on there, and said ‘I’m writing this!’, being typical Freddie. And we all played on the original, but you kind of wouldn’t know it because it’s very much a disco format.” In the end, the Queen recording of ‘Love Kills’ ended up on the Metropolis soundtrack under Mercury’s name, and hit the Top 10 hit in the singles chart in the autumn of 1984. (Chart space was shared with ‘Together in Electric Dreams’, another of Moroder’s memorable collaborations, this time with the Human’s League’s Phil Oakey.) Ostensibly, the compromise reached by both parties was that Queen, in exchange for leasing ‘Love Kills’ to Moroder, could utilise parts of the Italian producer’s Metropolis footage in the video for their next single. (‘Love Kills’ was later reworked for 2014’s Forever compilation, which also included a William Orbit mix of ‘There Must Be More to Life Than This’, Mercury’s duet with Michael Jackson.)

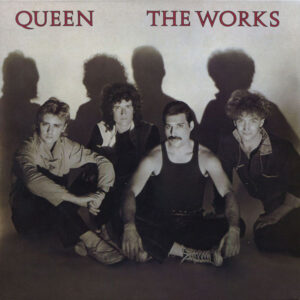

The band began recording their eleventh studio album, The Works, between August 1983 and January 1984, with work completed at both Musicland Studios and The Record Plant (Los Angeles). True to form, the sessions were often tense, with May later admitting he walked out on more than one occasion, but there was a consensus within the band that Hot Space had been a mistake, and, as Deacon confirmed to The Hit magazine’s Martin Townsend in 1985, there was something of an eagerness to go back to basics: “We really did talk about how we were going to attack the next album. With The Works we decided to go more towards the things people actually associate with Queen.” Certainly, both ‘Tear it Up’ and ‘Hammer to Fall’ succeeded in restoring the band’s hard rock credentials, while ‘It’s a Hard Life’ reaffirmed the band’s classical influences, subtly borrowing its intro from Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci opera. Additionally, the acoustic ‘Is This the World We Created?’ saw the band at their most stripped back since ‘Love of my Life’ in 1975, while ‘Man on the Prowl’ found them revisiting rockabilly terrain first inhabited by 1979’s Elvis Presley-inspired ‘Crazy Little Thing Called Love’.

However, as May told Sounds magazine in 1983, while the box-ticking album did, to a certain extent recapture some of the band’s former glories, their willingness to experiment in the studio was still prevalent. One of their newest ‘toys’ was a then-fashionable Fairlight CMI [Computer Music Instrument], a highly advanced – and commensurately expensive – digital workstation that enabled users to store recorded sounds and alter their pitch via its digital synthesiser. “We’ve dabbled with the Fairlight,” he explained, “but we haven’t gone totally toward making machine music because the fact is we don’t like it! The human element is very important.” Certainly, Taylor and May’s ‘Machines (or “Back to Humans”)’ boasted one of the band’s most electronic productions to date, not only utilising the expensive sampler, but also showcasing the vocoder function of a Roland VP-330 synth. (Described by its manufacturer as ‘the first keyboard instrument to elevate vocoder technology above the realm of gimmicks’, Taylor had previously used the instrument both on ‘A Human Body’, the frequently overlooked B-side of ‘Play the Game’ and his Fun in Space album, notably ‘Interlude in Constantinople’, which recalled Emerson, Lake and Palmer at their most bombastic.) “Brian wanted to make it a battle between the human side by using the real drums and guitars etc, and a totally synthetic side, the machines you know – the drum machines and the synthesisers and the Fairlights,” Taylor explained to the US DJ Jim Ladd in 1984. “So the thing is meant to be a battle between the two, with the idea of basically going back to humans.” To a certain extent, the experiment worked, but there were some decidedly questionable lyrics on offer – “What’s that machine noise / It’s bytes and megachips for tea / It’s that machine, boys / With Random Access Memory” – and an instrumental 12” mix, that weaved in elements of ‘Goin’ Back’ (recorded under the Larry Lurex moniker in 1973), ‘Ogre Battle’ (1974) and ‘Flash’ (1980) was, arguably, more palatable to listeners. Taylor later admitted that the band’s flirtations with the new technology was a mistake. “I think we got bogged down in the studio,” he told Q magazine in 2005. “There was always a new machine back then – and they were all out of date and being used as coffee tables within six months. Blame the 80s. There was a lot of awful, dreadful shit in the 80s.”

INVADED BY MARS

Of course, ‘Machines (or “Back to Humans”)’ wasn’t the only new Queen track to feature a smorgasbord of synths and robotic voices. There was also the opening cut, ‘Radio Ga Ga’ which was released as a single in January 1984, their first 45 since ‘Back Chat’ in August 1982, and the first to carry a personal catalogue number (QUEEN1). However, this veritable milestone of the band’s back catalogue would boast a far more successful juxtaposition of the electronics and the more traditional sounds that Queen fans readily identified with. However, the single’s B-side – May’s throwaway rock parody, ‘I Go Crazy’ – was less successful. “It was very rough and raw, but I really liked the sound,” May told Faces magazine in 1984. “The other three hated it so much they were ashamed to play on it.”

The release of ‘Radio Ga Ga’ would also mark Taylor’s debut as a hitmaker. (Somewhat surprisingly, if you ignored the US-only ‘Calling All Girls’ in 1982, it was also the first song of the drummer’s to be released as a single.) Certainly, in terms of the band’s songwriting, Mercury and May had done much of the heavy lifting since Queen’s formation in 1970, but that’s not to say that both Deacon and Taylor weren’t capable composers themselves. Deacon had already penned hits such as ‘Another One Bites the Dust’, ‘Spread Your Wings’ and ‘You’re my Best Friend’, while Taylor had contributed worthy material to every album since their self-titled debut in 1973, including the classic ‘I’m in Love with My Car’, which, to his considerable financial benefit, had also doubled up as the B-side of the ubiquitous ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. Like May, the husky-voiced drummer was also a competent singer, often singing the lead on his own compositions, as well as contributing incredible falsetto parts to his bandmates’ songs (see ‘My Fairy King’, ‘Father to Son’, the aforementioned ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ and the astonishing intro of ‘In the Lap of the Gods’). However, it would be an enthusiastic Mercury who would take the lead on ‘Radio Ga Ga’. (It’s arguable whether there was another singer on the planet who could deliver such a decidedly twee chorus – “All we hear is radio ga ga / Radio goo goo / Radio ga ga” – with such conviction.)

Something of a statement on the emergence of MTV and the diminishing use of radio (“We hardly need to use our ears”) , the inspiration for the title of ‘Radio Ga Ga’ had come from an unlikely source. Taylor’s toddler son, Felix, had described a song he’d heard on the radio as “ca ca” (French for poo), and this provided the cue for Taylor to begin working on the track. “It deals with how important radio used to be, historically speaking, before television, and how important it was to me as a kid,” he explained to Modern Drummer magazine in 1984. “It was the first place I heard rock ‘n roll. I used to hear a lot of Doris Day, but a few times each day, I’d also hear a Bill Haley record or an Elvis Presley song. Today it seems that video, the visual side of rock ‘n roll, has become more important than the music itself – too much so, really. I mean, music is supposed to be an experience for the ears more than the eyes.”

Like the Buggles’ similarly-themed ‘Video Killed the Radio Star’ (the Russell Mulcahy-directed video of which, tongue-firmly-in-cheek, had been the first to be played on MTV on 1 August 1981), they’re overtly nostalgic, recalling a bygone era of rousing parliament speeches – “You’ve yet to have your finest hour” was a continuation of Taylor’s apparent interest in Winston Churchill, having already used one of the former Prime Minister’s well known phrases, ‘Action This Day’, in a song title – and heart-racing drama broadcasts (“Through wars of worlds, invaded by mars”). In the case of the latter, the reference to H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds consolidated the songwriter’s fondness for science fiction, first evidenced by the striking sleeve of 1977’s News of the World – which featured an updated image of a robot by the American artist Frank Kelly Freas – and later on his work on both the Flash Gordon soundtrack and his debut solo album, Fun in Space, which featured a goggle-eyed robot on the sleeve. Later, in the video for 1982’s ‘Calling All Girls’ single, there was even a parody of George Lucas’s dystopian debut, THX 1138. (May, too, was a huge sci-fi fan, while Mercury, despite lyrics to the contrary in 1978’s ‘Bicycle Race’, did like Star Wars.)

Taylor would later claim that he usually set aside his more ‘personal’ songs for his solo albums, but, after locking himself away for three days and demoing ‘Radio Ga Ga’ –using little more than a Jupiter-8 synthesiser and a LinnDrum – his bandmates quickly seized upon its commercial potential, with Mercury enthused enough to help with the song’s final arrangement. When it came to recording the track for real, it was Fred Mandel – who had played on the Star Fleet Project mini-album – who programmed the synth-bass using the Jupiter-8’s built-in arpeggiator, while the track’s robotic vocals were derived from Taylor’s VP-330 synth. However, whilst the song was certainly technology-heavy, a slide guitar solo from May, as well as Deacon’s intermittent live bass ensured there was a ‘human’ element in the finished recording.

Despite its considerable length – at 5:47 it was the band’s longest single since ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ – the song was perfect for radio, and there was a suitably lavish video (ironic, given some of the song’s negative connotations) to match. Helmed by ‘Under Pressure’ director David Mallet, who had previously worked with, among others, Blondie and Peter Gabriel, the clip was filmed at Shepperton Studios in Surrey in November 1983, at a cost of over £110,000. It was certainly Queen’s most expensive promo to date, and it featured 500 extras – members of the band’s official fan club – who dutifully donned white boiler suits for the now-iconic clapping scenes (described later, somewhat unfairly, by New Musical Express as ‘vile, fascist imagery’). As well as incorporating scenes from Metropolis, the band were seen flying in a purpose-built car, with Deacon’s then-new, oversized perm comically flapping in the synthetic breeze. The memorable clip later received an MTV award nomination for ‘Best Art Direction’, eventually losing out to the Godley and Creme-directed clip for Herbie Hancock’s electro classic, ‘Rockit’. “I enjoyed that video,” Taylor told Jim Ladd in 1984. “I thought it was one of our better videos and was one of the best we’ve ever done. And was great to have the opportunity to work with the Metropolis footage, which had been a favourite of mine for years.” The video’s call-and-response clapping would soon transcend to the band’s live shows and, at Live Aid in July 1985, it was one of the highlights of their triumphant, show-stealing set. “I’d never seen anything like that in my life, and it wasn’t calculated, either,” May told Mojo magazine in 1999. “Everybody thinks that everything about Queen was calculated and sure, some of it was. We weren’t stupid. We understood our audience and played to them. But that was one of those weird accidents, because of the video.”

ARROGANT NONSENSE

BUY NOW

At the time of its release, an unforgiving New Musical Express dismissed ‘Radio Ga Ga’ as “arrogant nonsense”, claiming it lacked “substance, intention, cohesion or spirit”, while Sounds magazine’s Sandy Robertson declared in her three-star review of The Works that it was a “prime-slime example of the humming, annoyingly likeable baby-food pop music that the song itself is slating”. Nevertheless, it was a worldwide smash hit, hitting the top spot in 19 countries. It was the 26th biggest selling single in the UK in 1984, and the sixth biggest selling of the band’s career on their home turf, eventually outselling other acknowledged classics such as ‘Killer Queen’ and ‘Somebody to Love’. Originally released on 23 January 1984, it entered the chart at No.4 and, during its 11-week chart run, it peaked at No.2, with only Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s classic ‘Relax’ single depriving them of a well deserved third chart-topper. In the US, however, it became the band’s last single to reach the Billboard Top 20 until the sad advent of Mercury’s death in November 1991. Queen had already lost a large chunk of their audience after the Hot Space album, and their commercial fate was sealed with the controversial promo clip for Deacon’s ‘I Want to Break Free’. The hilarious video saw all four members dressed in drag as they sent up the long-running British soap, Coronation Street, but the joke was lost on the US public and the single limped to No.45. Whilst The Works and its attendant four singles – each penned by a different member of the band – were huge hits in Europe, Queen’s first album for their new American label (Capitol) was a relative failure, resulting in the cancellation of a tour in this lucrative marketplace.

Since its release in the winter of 1984, the popularity of ‘Radio Ga Ga’ continues to endure, and it’s still an immovable part of the current Adam Lambert-fronted incarnation of the band’s live set. Back in 2004, quirky Michigan rock band Electric Six also bagged a Top 30 UK hit with their version of the iconic track, while a certain Stefani Germanotta, who was a big Queen fan, derived her stage name of Lady Gaga from the song. (May reciprocated the interest by playing guitar on the ‘Poker Face’ singer’s 2011 ‘You and I’ single, which also sampled his ‘We Will Rock You’ anthem.) As for the original sentiment behind the song, MTV may not be as popular as it used to be, but the advent of YouTube has further popularised the video medium, with the band’s pioneering ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ clip registering over a billion views. (To date, ‘Radio Ga Ga’ has been viewed almost 250 million times.) However, the popularity of radio shows no sign of waning, and this, coupled with a rising interest in podcasts and audio books, has ensured that we still “need to use our ears”.

The 40th anniversary edition of Queen’s Greatest Hits is out now.

Brian May will release an expanded and remastered version of his Back to the Light album on 6 August.

Roger Taylor’s sixth solo album, Outsider, will be released on 1 October.

- QUEEN’S MACHINES – How Music Changes Through The Years (1979 – 1984) - July 25, 2021

- SUGAR RUSH – The Story of ‘Sugar Tax’ - May 7, 2021

- Survival – The Story Of ‘Machine and Soul’ - April 30, 2021