“I realised my future was electronic.”

Perhaps one of the most significant things about reading Dave Ball’s autobiography is realising how much it captures a golden age in music history. Not just for the story of iconic synth-pop outfit Soft Cell, but also of a lost pre-internet era of glamour and excess where financial success from musical endeavours was the standard. Many of the foundations of that industry have gone and, in some cases, a number of the legendary characters that Ball talks about have also sadly passed away in the years since.

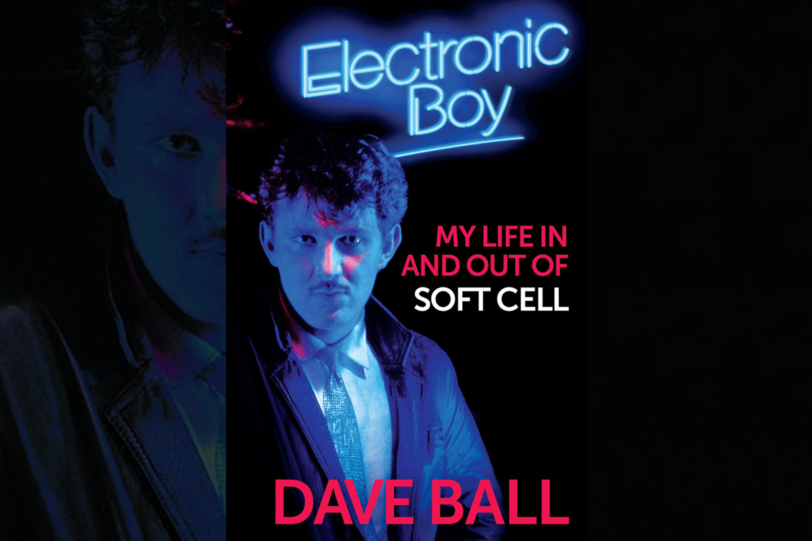

There’s something particularly timely reading Electronic Boy during the 40th Anniversary year of Soft Cell’s classic album Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret (see TEC feature previously). Consequently, it provides an engaging window on the recording of that album, as well as casting a wide net over the synth-pop duo’s extensive musical history. The book also stands as a companion piece of sorts to Marc Almond’s own autobiography, 1999’s Tainted Life. On that basis, it’s intriguing to see how different both musicians view their combined success.

Electronic Boy also offers a detailed look at Dave Ball’s formative years; a colourful background which not only tracks his initial interest in music, but also looks at a life marked with some profound sadness and tragedy delivered with remarkable candour. Growing up in Blackpool, it was inevitable that the young Ball would be exposed to the popularity of northern soul. But a stint in the ice cream business also exposed the future Soft Cell founder to Kraftwerk’s Autobahn for the first time (thanks to a friend’s portable cassette player). “That hour in the ice cream factory was a pivotal moment when two kinds of music I really liked began to fuse in my mind, like a mathematical algebraic equation or a recipe: northern soul + synthesisers = XYZ?”

The book is peppered with plenty of witty anecdotes, which serves to embellish the hidden character of Soft Cell’s quieter member. Acknowledging an early love for cinema, Ball expresses a fondness for films such as Oliver! and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. “My favourite characters were usually the baddies like Bill Sykes and the Child Catcher – come to think of it, they could almost have been the prototypes for a certain synth duo.”

Other stories include the realisation that ‘Bedsitter’ may have confused some non-domestic music fans (“Most people outside the UK wouldn’t know what a bedsit was”); mistaking Van Morrison for a minicab driver and Vince Clarke asking Ball not to use a Roland 909 on a Grid remix of an Erasure track due to over-familiarity of the sound at the time. The book also drops into travelogue mode at times, including some tales of a flight-nervous Ball taking passage on container ships. Even though the sea-bound journeys are mostly uneventful, Ball manages to lend these stories a sense of adventure that offer an interesting contrast to the pop star lifestyle.

The book is also not averse to delivering some axe-grindy angst when the occasion demands it, such as Ball’s frustration at the manufacturers of Soft Cell’s initial Mutant Moments EP. A catalogue of errors, including missing sleeves and constant delays, prompts Ball to vent in the book over the experience: “When ‘Tainted Love’ was number one all over the world they even had the cheek to send me a fucking Christmas card!”

BUY NOW

Naturally, the Leeds Polytechnic years are covered in detail, providing some fascinating insight into the circumstances that launched Soft Cell. This includes zoning in on the sound studio that the venue housed (“I positioned myself right next to it so I always knew what was going on”). But also Ball’s enthusiasm running away with him at times, such as borrowing future-Fad Gadget Frank Tovey’s Crumar Compac piano without his permission to record some initial tracks (“[he] never forgave me”).

As a matter of course, the book explores the success of ‘Tainted Love’, as both the triumph and the ‘albatross around the neck’ that the single became for the duo. But the analysis of the song’s composition provides some fascinating background to it’s now-classic sound: “Marc had two Pearl Syncussion electronic drumheads and a Synare electronic drum that created ‘Tainted Love’s distinctive ‘bink bink’ sound when enhanced through Mike [Thorne]’s DeltaLab DL-4 on a very short clangorous delay, making it more metallic.”

There’s also plenty of stories from Ball’s post-Soft Cell years, including finding success with electronic dance outfit The Grid. It offers an opportunity for Ball to ponder on his ability to combine unusual ideas (“Northern soul + electro = ‘Tainted Love’, bluegrass + electro = ‘Swamp Thing’, both million sellers”) as well as moving into a world beyond the classic synth-pop era. Naturally, there’s plenty of anecdotes from this period, some suggesting a fortunate twist of fate: During a Japanese tour for The Grid in 1995, they had just left Tokyo when news of the Aum Shinrikyo terrorist attack broke.

The story comes full circle when it rotates back onto Soft Cell’s re-emergence, including their (not quite) final 02 performance in 2018, which Ball remarks on with some typical blunt commentary (“My monitors sounded absolutely shit, all the levels were wrong and it was difficult to hear what I was playing…”). The book closes with Ball looking ahead to future Soft Cell adventures, including a brand new album (which eventually became forthcoming release *Happiness Not Included).

Electronic Boy manages to strike a balance between an engaging story, as well as appealing to the more technically-minded music fan (it includes a detailed list of Ball’s synthesiser arsenal at the end of the book). Aside from the odd error, Dave Ball’s autobiography emerges as one of the more entertaining and informative books of the classic synth-pop era.

Electronic Boy: My Life In and Out of Soft Cell is out now.