“Musically, we went through a bunch of phases – for a while it was rock opera. We were going to compose some grandiose stuff about earthquakes in Guatemala. Our ambitions had no limits.” – Paul Waaktaar-Savoy

It’s been well documented that a-ha’s huge success with ‘Take On Me’ – and subsequent album Hunting High And Low – didn’t happen overnight. Whilst the band didn’t slog it out via the conventional – and slightly clichéd – live route, they chose instead to hone their songwriting craft in the studio; using the fast-developing advances in electronic instrumentation to develop their sound.

But that’s not to say the band didn’t have any grounding at all in live performance – in truth, the three members of a-ha had all paid their dues, completing a musical apprenticeship of sorts in a number of bands.

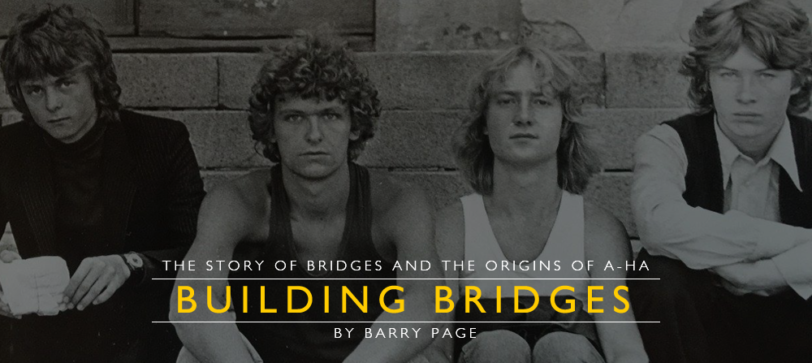

Prior to a-ha’s official formation on Morten Harket’s 23rd birthday in September 1982, Paul Waaktaar-Savoy and Magne Furuholmen had recorded two albums as part of a four-piece combo named Bridges, including a self-financed opus titled Fakkeltog (which translates as ‘torchlight procession’). In this article we tell the story of Bridges, using archive material and some exclusive reminiscences from former members of the band.

Far from being prototype a-ha recordings, the music of Bridges owed more to the music of The Doors than the synth-pop sounds that would characterize much of the Norwegian trio’s earliest demos and album recordings. Brimming with ambition, the band’s only officially released album Fakkeltog is a surprisingly complex piece of music; split into three parts and boasting an impressive mastery of several instruments, progressive rock-like time signature shifts and lyrics inspired not just by Jim Morrison, but also Norwegian literary figures such as Gunvor Hofmo. Perhaps more importantly, the roots of many of a-ha’s songs stemmed from Bridges sessions and recordings, including ‘Take On Me’, ‘Scoundrel Days’ and ‘Soft Rains Of April’.

It would be very difficult to understate the huge influence of The Doors on the music produced by Waaktaar and Furuholmen. As key an influence as David Bowie on the ‘Blitz Kids’ of the late 1970s or Kraftwerk on electronic acts such as OMD and The Human League, much of the music of a-ha (particularly throughout the 1980s and 1990s) is permeated with Doors influences. There’s the earlier brooding numbers such as ‘Here I Stand And Face The Rain’ and ‘Soft Rains Of April’; through to the roadside drama of ‘Sycamore Leaves’ and mid-period numbers such as ‘Slender Frame’, ‘Early Morning’ and Lamb To The Slaughter’ that all imbue a Venice Beach campfire spirit. In concert the band regularly included a snatch of ‘Riders On The Storm’ during ‘Cry Wolf’.

Building Bridges (1974-1979)

Pål Waaktaar Gamst and Magne Furuholmen had become acquainted circa 1974 as near-neighbours in Manglerud, a borough that lies in the southeastern district of Oslo. Waaktaar reflected on their early meetings years later: “He was unbelievably musical, and we hit it off right from the start. He had a Dali amplifier – with a tremolo. It was the coolest thing we’ve ever heard – the first time you hear a tremolo, it’s a fantastic sound. Magne played ‘Sunshine’ by Nazareth, and we were really impressed.”

In 2013 Furuholmen told music writer Wyndham Wallace about an early encounter with Waaktaar: “I saw him perform on a third floor balcony. They were performing inside, but there was a group of people stood outside, and they’d come out and he’d put the drumsticks in the air. I think it was just a Hammond, a living room organ, and cardboard drums – a very makeshift concert – but I remember being incredibly impressed, not by the music but by the spectacle of it all.”

Both teenagers had grown up with music coursing through their veins; Furuholmen in particular. His father Kåre was a well-travelled musician, playing trumpet for the Bent Sølves Orkester, a popular six-piece jazz band. Sadly, he (and the rest of his entourage) died in an airplane crash on the way to a show in Sweden in May 1969. Bizarrely, the tragedy was witnessed by a nine-year old Morten Harket. Furuholmen told the Adresseavisen newspaper years later: “The first time I met Morten Harket, we walked home together after a party. It was a long walk, and when we had talked about the important stuff – what music we liked – we needed to find other topics of conversation. What our parents were doing, things like that. I told him that my father died in a plane crash in 1969. Morten remained completely silent for a while, before he told me that he was an eyewitness to the plane crash in Drammen… he saw the plane hit the ground.”

The teenagers had a shared love of both Jimi Hendrix and The Doors, as Waaktaar recalled during a Facebook Q&A in 2015: “When I first started playing guitar, I learned from copying old blues vinyl played on half speed. Jimi Hendrix was an early hero – Magne and I would compete who had the biggest collection of obscure bootlegs. Mind-blowing stuff. Then it was all about The Doors and Robbie Krieger who just knew exactly what each song needed and without ever over-playing.” And it probably wouldn’t have gone unnoticed that, while Jim Morrison garnered most of the attention as The Doors’ frontman and in-house poet, it was guitarist Krieger that had quietly contributed some of the band’s best songs (see ‘Light My Fire’, ‘You’re Lost Little Girl’, ‘Touch Me’, ‘Love Her Madly’, etc). Waaktaar also practised at an after-school club, playing folk songs such as ‘Hang Down Your Head Tom Dooley’.

The fashions of the Sixties also had something of an effect on Waaktaar: “I wore wide bellbottoms, grew my hair long and put up Jimi Hendrix posters,” he told Tor Marcussen in The Story So Far. “At Nordstrand, the boys were all clean, crew cut kids driving around in their rich fathers’ cars. Everybody else’s style was completely alien to me, and I had no desire to become like them. I’ve always wanted to be different.” Much to his parents’ disappointment, the increasingly music-obsessed Waaktaar harboured little in the way of academic ambition (he was even nicknamed “The Guest” by his teachers due to his poor attendance record!). “They came from Northern Norway to Oslo to get an education, and had to uproot themselves from their families up there,” he recalled. “My not wanting to go to University and take the same route was a bit of a downer for them.”

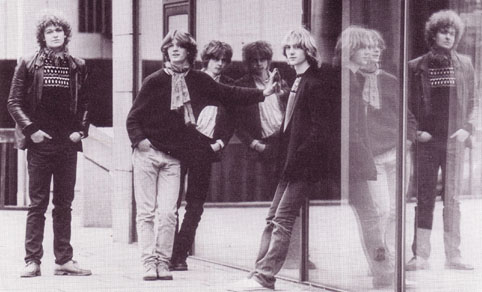

Both Waaktaar and Furuholmen had been in different school bands, including Black Day and Black Sapphire, respectively. Waaktaar confirmed that the competitive streak between the pair was prevalent even at this early stage in their music career: “We were always in there together, competing to write the best songs, play the fastest guitar.” The pair initially teamed up in the band Spider Empire, with Furuholmen on vocals and guitar, before changing their name to Thala and the Layas Blues Band and then, finally, Bridges, in 1978. “During that period Magne and I went though different band names from one month to the next,” Waaktaar told The Electricity Club. During a speech in 2012, Bondi recalled the first time he met Waaktaar and Furuholmen: “I got off the bus, carrying a bass guitar – that is how I meet Magne and Paul for the first time. Two long-haired boys – or were they girls? – dressed like Jimi Hendrix. Silk flower shirts, bell-bottom pants, moccasins, long scarves, handkerchiefs – I was catapulted back to the sixties!”

The band, which was known for a while as ‘The Bridges’, eventually reverted to a four-piece with Waaktaar in a dual guitar and vocal role, while Furuholmen was persuaded to take a Ray Manzarek-like position behind the keyboards; the fledgling songwriter keen on guiding the group in a Doors-like direction. Whilst not as rich in tone, Waaktaar possessed a baritone voice akin to that of Jim Morrison’s, and his rockier vocal tones would perfectly suit his later indie-pop work with Savoy during a-ha’s sabbatical in the mid-to-late 1990s. I asked Hagelien if he was as enamoured with The Doors as Waaktaar and Furuholmen. “I always said that the songs composed by Magne and Paul at that time was much influenced by The Doors,” he replies. “I believe Jimi Hendrix was important for them too, and probably also The Beatles. Magne and Paul gave me the book The Beatles: In Their Own Words for my 17th birthday. I was, and Viggo too, more of a prog rock lover, listening to artists like Rick Wakeman, ELP, Yes, Genesis and Frank Zappa. We also loved what we called ‘jazz-rock’, like Mahavishnu Orchestra. I really was a fan of the drummer Phil Collins, both in Genesis and Brand X, Carl Palmer, Billy Cobham and Terry Bozzio.”

By the time of Bridges’ formation, the well-travelled Furuholmen had moved to Asker, which was within a commutable distance from Manglerud. And it was the basement at Furuholmen’s family home in Asker, affectionately referred to as Knusla Bruk, that provided the rehearsal space for the ambitious young band during their high school years. They focused on practising original material rather than covers, while Waaktaar wrote his lyrics in English rather than his native Norwegian, later explaining that “there was no point trying to shove Norwegian down English people’s throats.”

After-school sessions were frequent and Waaktaar was beginning to stockpile a vast repertoire of songs, as Bondi later recalled: “The only homework we did during high school was what we assigned ourselves – or, more accurately, what Magne and Paul assigned one another. A new song for every practice. The result was a huge number of songs: ‘Truths Of Love’, ‘The Endless Brigade’, and so on. The list is incredibly long. Songs about dreams… songs as musical building blocks for what would later become a-ha.”

Whilst Waaktaar’s chosen career path had been met with disappointment, he certainly found an ally in his older sister Tonje who would spur him on during this period and throughout his musical career. In the Furuholmen household, Magne’s mother Lise was also a constant source of encouragement. “There was always a woman behind the band – Lise,” recalled Bondi. “With four rehearsals every week for four years, three teenaged boys not only moved into her house, they moved into her refrigerator! She also had four children of her own. We weren’t given many responsibilities, but at one of the first practises, we were sent out to the potato field! Lise is a teacher, but she never asked us if we had done our homework. It was as though she understood that something big was happening.”

Hagelien was also able to share some memories from this period: “Paul came all the way from Manglerud to Vollen every Friday after school,” he says. “He stayed there for the whole weekend. Viggo and myself showed up on Saturdays and Sundays. There was a 25-minute walk from Hvalstad (where Viggo and I lived in Asker) to the bus stop and another 25 minutes from the bus stop in Vollen to Magne’s house. We practised mostly every weekend and Magne’s mother always served us good food – we felt very welcome. It was a big house with a large room in the basement where we played, and my drums stood permanently. Over time I damaged the very nice and brand new wooden pine floor with my drum hardware spikes – I felt very embarrassed! Per Arne Skjeggestad, an old friend of Magne and Paul, occasionally joined us in parts of the weekends – he was following the band and took a lot of pictures.”

Bridges In Concert (1979)

Live performances were sporadic during the infancy of the band’s career and, years later, Waaktaar vividly recalled his first performance: “I started, you know, on drums, because that was the most invisible place in the band. But then songwriting suddenly reared its head, and the urge to present the songs became so strong that it literally pushed me forward to the edge of the stage. I remember the day I turned on the microphone and sang – it was a big deal for me.”

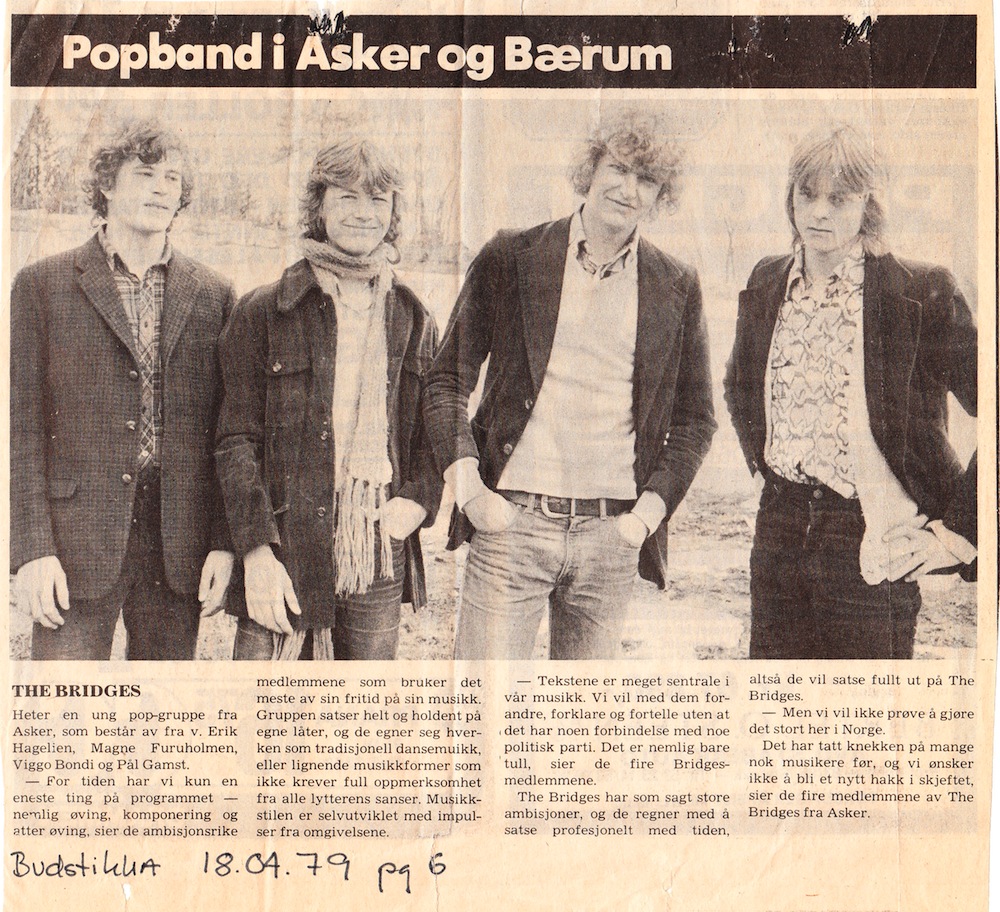

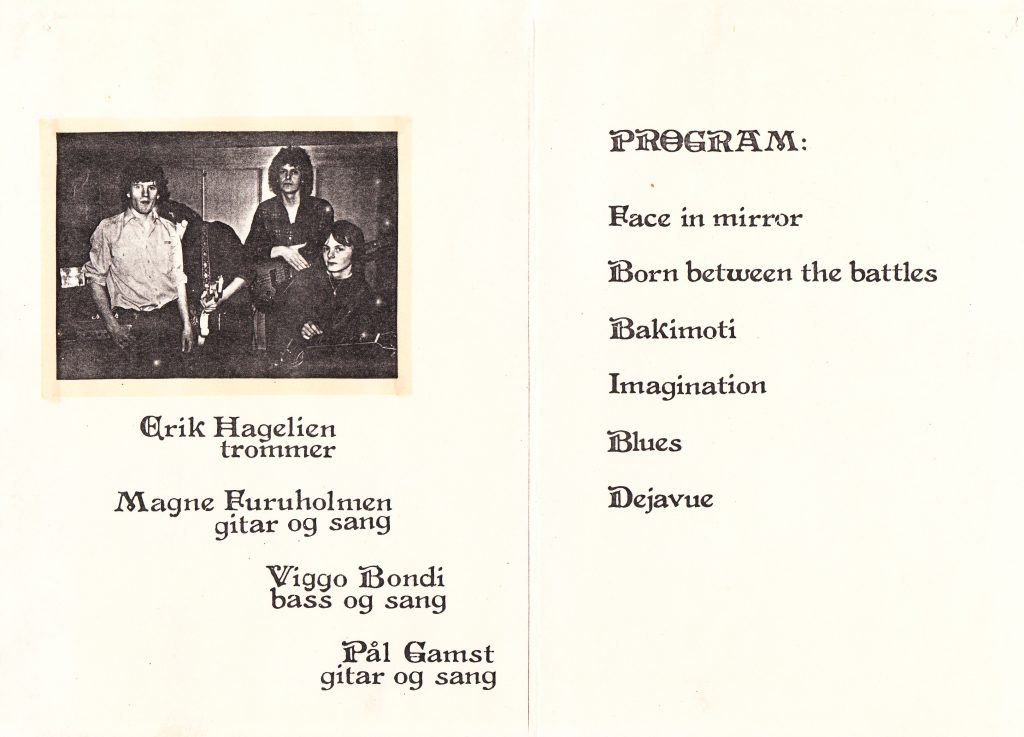

One of the band’s first live commitments was NM for Rockeband (a Norwegian ‘battle of the bands’) at Chateau Neuf in Oslo. The performance of ‘Somebody’s Going Away’ during the preliminary heat on the 11th March was, according to some sources, beset with sound problems and the band didn’t progress to the next round on the 12th (Oslo-based Broadway News prevailed as the winners at the national final in July). The following weekend the band played a private show for family and friends at Hagelien’s home in Hvalstad, and also went to the trouble of preparing a small programme for the event! This fascinating document reveals that Waaktaar was still using his original surname of Gamst, while the set list included songs such as ‘Born Between The Battles’ and ‘Imagination’. Keen to boost their profile, the ambitious band were also interviewed by local newspaper Asker og Bærum Budstikke in April. “We do not want to make it big here in Norway,” they said. “We do not want to be a new notch in the joke.”

Chateau Neuf also provided the setting for another live show, performing with several other bands as part of a programme organised by the IAB (an amateur band association) on the 27th May. According to Hagelien, the band performed well during the day-long event.

One of the new line-up’s most important engagements, certainly in terms of the formation of a-ha, was a performance at Asker Gymnasium in 1979. Bondi picked up the story years later: “On the way to the concert, Terje Nøkleby – Magne’s stepfather – played a tape recording of the previous weekend’s jam session. It sounded dreadful. We were in shock – were we really that bad? We could not live with that. It became one of our best concerts ever… but, more importantly, among the audience in the hall was Morten Harket.” The future a-ha vocalist was certainly impressed by the performance: “It really stunned me when I heard them live – this was Doors music,” he told Wyndham Wallace in 2013. “All of a sudden everything changed – it stunned me, right there on the floor. ‘This is it. This is how it’s gonna happen.’ It was instant. But at the same time I knew they needed me. I had to be a part of it. That wasn’t a question for me. It wasn’t an issue. It wasn’t a problem. It was just a fact, a comfortable matter of fact. But I was not going to go after them and suggest anything. I just knew, and that was enough for me. So I left it there. For quite some time.” Harket did in fact approach Bondi about joining the band, but the timing was wrong, and the future a-ha vocalist would have to ply his trade in the band Souldier Blue for the foreseeable future. World domination had to be put on hold…

In the spring of 1980, the confident band played a show at the Dovrehallen club in Oslo, sharing the bill with a local punk rock band named Kjøtt. “The punks waltzed to Bridges’ music – we did not take that as a compliment” recalled Bondi. The show was etched in his memory as he also recalled that a few days later his ears pricked up when he received a phone call from Ole Sørli, formerly of Polydor Records. “We were in shock – this would mean a record contract! Or so we thought. Instead, he produced two black and white pictures of two teenage girls with huge sunglasses: Ingrid and Benedicte. Dollie de Luxe had just recorded their first album, and he asked if we wanted to be their backing band! We left his office, infuriated. We’d been given one of their records and, once we were out on the street again, we found out that it performed really well as a frisbee!”

Fakkeltog (1980)

“I grew up in the Sixties/ The Seventies I betrayed/ But the Eighties are mine/ You can’t take them away from me”

Following their flirtations with live performance, the next logical step was to cut a record; and fate was to play another part in the Bridges story with their choice of record producer. Svein Erichsen was both a neighbour of Furuholmen’s and a fan of The Doors (he’d seen them play at the Isle of Wight Festival in August 1970), and – crucially – possessed technical knowledge. “As I recall, he didn’t do much as a producer… we did that mostly ourselves,” says Jevanord. “[He was] more of a fan, and neighbour of Magne’s. Anyway, he was credited as a producer on the album because he helped us with various equipment in the period before Fakkeltog. For example, a 4-track recorder to get down the old songs Bridges had made. Mags can probably tell you more about his musical background, because I don’t know. I know he was a guitar / bass player… oh yes, he did some background vocals on a track on Fakkeltog as well.”

It would take the well-rehearsed band just a week to record the album, at a cost of 500 krone per day, and the sessions were long and productive. “We prepared all the arrangements at the rehearsals, so we used just four days to record the main [album]” recalls Jevanord. “The rest of the week we did the overdubs, vocals and mix. Fakkeltog was finished in one week in other words. But of course, some changes were also done here and there in the studio.” I asked Jevanord if there were any creative tensions between Waaktaar and Furuholmen at this early stage. “No, just minor, healthy disagreements all musicians experience during making good music together – four strong personalities,” he replies. “So, no, not like I’ve heard it has become in late a-ha-days!”

Waaktaar’s guitar of choice was a Gibson SG (a model favoured by Robbie Krieger), while Furuholmen’s keyboard setup included a Wasp synthesizer and a Moog Polymoog (203A) synthesizer. The Wasp synth (a favourite of Duran Duran’s Nick Rhodes) was a quirky but affordable instrument that was launched by EDP (Electronic Dream Plant) in 1978, and is easily identifiable by its yellow and black colours and unconventional flat keys. The considerably more expensive Moog, meanwhile, dated back to 1975 and featured a number of presets (including harpsichord, piano and organ) and was important to the band, in that it was capable of emulating some of The Doors’ trademark sounds. One notable user of the 203A was Rick Wakeman, who’d used the instrument on some of Yes’s recordings in the late 1970s, while Gary Numan used a more affordable version of the Polymoog (the 280A) to great effect with the iconic Vox Humana preset.

The band also used some additional musicians to augment some of the songs, including strings on the beautiful ‘Vagrants’ (the 4-piece string section included Hans Morten Stensland, who later featured on a-ha’s Foot Of The Mountain album in 2009).

Though unarguably derivative in places, the resulting album is a perfect representation of where the band were at that point. What is really impressive, though, is that the album was cut by a band largely in their late teens and barely out of school (Furuholmen was just 17). Certainly the quality of the musicianship shines through – Bondi’s bass lines are melodic, while Jevanord’s drum playing is adventurous but tight (check out the album’s superb 10-minute centrepiece, ‘The Stranger’s Town’, that showcase a range of skills). But it’s the combination of Waaktaar’s inventive guitar work and Furuholmen’s broad palette of keyboard sounds that characterizes much of Fakkeltog; a sound that was more in tune with the progressive rock genre than the Punk and New Wave sounds that were coming out of the UK and the USA in the late 1970s. Norway had its own progressive rock movement, spearheaded by early ’70s acts such as Saft, Aunt Mary and Popol Ace, but it was a scene that was becoming increasingly unfashionable as the decade wore on.

Whilst Fakkeltog wasn’t quite in tune with the musical trends of the day, the band certainly weren’t alone in their affinity for The Doors’ music – acts such as The Stranglers, Echo and the Bunnymen and The Triffids were all clearly influenced by the Los Angeles rockers. It would be cruel to dismiss Fakkeltog as nothing more than a Doors tribute album, though. Certainly the spectre of the Lizard King looms large: ‘Death Of The Century’ and ‘Vagrants’, portents of Waaktaar’s favoured ballad style with a-ha, echo the mournful and melancholic side of Morrison’s baritone, while the spoken word elements of ‘Every Mortal Night’ recall ‘The WASP (Texas Radio And The Big Beat)’ from 1971. Waaktaar’s guitar playing, whilst not as effortlessly dextrous as Robbie Krieger’s, is certainly impressive and you can hear The Doors guitarist’s influence on tracks such as ‘Somebody’s Going Away’, which feature some fine blues licks.

There were some other key literary references on Fakkeltog as well: Gunvor Hofmo was a reclusive writer who lived in the Nordstrand area of Oslo, publishing several poetry collections. “She was the closest you could get to The Doors in Norway,” Waaktaar later claimed. “Early Bridges songs like ‘Guest On Earth’ were snatched straight out of her poetry collection Gjest På Jorden.” Waaktaar wasn’t alone in his admiration for the poet (who died in 1995) either – many years later, a Norwegian singer-songwriter named Susanna Wallumrød would record an entire album Jeg vil hjem til menneskene using Hofmo’s poetry.

In terms of the history of a-ha, there are two tracks that stand out: ‘May The Last Danse Be Mine’ [sic] and ‘Every Mortal Night’ both featured lyrics that were later recycled on the 1986 b-side ‘This Alone Is Love’, notably the melodic refrain “It will make my last breath pass out at dawn/ It will make my body dissolve out in the blue”. ‘May The Last Danse Be Mine’ was a track that dated back to the early days of the band, and represented a more romantic facet to Waaktaar’s writing. “That album is actually about my first real kiss,” Waaktaar later reflected. “About how at last I felt like a member of the human race. About how relieved and happy I was that it had happened – that someone wanted to be with me. About how I had grown up to the extent that I had thought it was rotten to be alone and about my disappointment when I realised how little she really was involved, but how something in me had been awakened anyway.”

The band had a novel way round of getting round the problem of presenting a three-part album across two sides of vinyl, as Bondi later recalled: “Sometimes Paul and Magne’s genius could get out of hand, such as when they decided that our first album should have three sides instead of two, with a stop-groove in the middle of one side… Very clever, but highly impractical!”

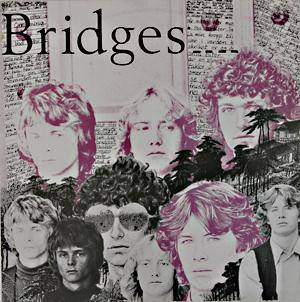

The album, which boasted a striking collage of band photos and lyrics on the front cover, was mixed by Svein Erichsen and Octocon owner Tore Aarnes. The band were confident that no major labels would show an interest in Fakkeltog, so they adopted the DIY ethos of British bands such as The Buzzcocks and released the album themselves on their own Våkenatt label (a name inspired by a Gunvor Hofmo poetry collection from 1954 titled I en våkenatt). Just 1000 copies were pressed, with the band shifting less than half of these units. I asked Jevanord what expectations the band had for the album, and how they promoted it. “Well, just the fact [we made] an album available, and get some reviews in some music papers and daily papers was fantastic – and most of them liked it,” he recalls. “All the promotion we did was to glue lots of posters all over Oslo city wherever we could, and we went around to the most popular record shops in Oslo and asked if they would like to buy some of them… some of them actually did!

Poem (1981)

Also involved in the making of the new album was former drummer Erik Hagelien: “Paul called me later, after I left, and asked me to join a studio recording,” he recalls. “One single song, ‘Våkenatt’, which I did and enjoyed very much. I recall that Paul’s sister and her boyfriend [Erik Nygaard] was in the studio and that a slide guitar was used.”

The band’s plans were derailed when an intruder broke into the recording studio and stole both the master tapes and Bondi’s Gibson Les Paul bass guitar. A distraught Waaktaar made an appeal to the Aftenposten newspaper in January 1981: “Those tapes couldn’t possibly be of any value to the thieves… But the recordings, the unfinished album, have cost us thousands that we’ve spent on studio time and work. Those tapes are worth so much more to us than the thieves. Can’t we please get them back?” Luckily, the plea proved to be successful and the stolen items were eventually returned. Tor Marcussen, a journalist with Aftenposten at the time, would later write The Story So Far, one of the first books about the band (published in 1986).

Around this time Waaktaar and Bondi travelled to London to pick up a synth-bass but, much to Jevanord’s annoyance, the pair returned with a set of expensive Pollard Syndrums! “I didn’t like it much,” he confirms. “Simply because the synth-drums in 1980 were terrible… more of a toy than an instrument. I used the analog Syndrums, and it was just another sound – like a bad drum machine. But I used them anyway on some tracks, just to please the other guys!” Syndrums were used by some well known acts, including The Cars and Yellow Magic Orchestra, but its primitive sounds soon went out of fashion; particularly following the introduction of the Simmons company’s range of far more authentic sounding electronic drum kits in the early 1980s (showcased by artists such as Duran Duran, Kajagoogoo and Ultravox).

Intent on steering their music in an electronic direction, Waaktaar sold his Gibson guitar. He told The Electricity Club: “I traded my SG for a Roland GR-300 guitar synth for the Poem album… Missing that awesome SG though… never seen a similar one since!” Guitar synthesizers were introduced in the late 1970s and Roland’s GR-300 had been officially endorsed by The Police’s Andy Summers, and used by other artists such as King Crimson and Robert Fripp. Roland enthusiastically described the product in one of their brochures: ‘The GR-300 polyphonic guitar synthesizer has an outstanding expressing ability, being able to reproduce the subtleness of the guitar sound which cannot be obtained by a keyboard synthesizer’. Sadly it didn’t quite live up to its billing and these days the vintage instrument is, like the Syndrum, more of a collector’s piece – Waaktaar soon reverted to guitar, primarily using a Gibson ES-335. Furuholmen, meanwhile, made a far greater investment with the purchase of a new Korg synthesizer; which was to prove far more conducive to their creative aspirations.

The pair announced plans to head to London in the hope of landing a record deal, but Bondi and Jevanord didn’t share their ambitions and declined an invitation to join them. Whilst artwork for the self-titled Poem album had been designed, its release was sadly shelved following the band’s inevitable break-up. Waaktaar and Furuholmen’s alliance with Harket was just around the corner, and a song that the duo had originally rehearsed with Bridges called ‘The Juicy Fruit Song’ would later morph into ‘Take On Me’, changing their lives forever…

Scoundrel Days (the post-Bridges years)

Jevanord, meanwhile, maintained a much higher musical profile and contributed to both the Scoundrel Days and Stay On These Roads albums, playing on key tracks such as ‘Cry Wolf’ and ‘The Blood That Moves The Body’. “We first did a demo version of ‘Cry Wolf’ in Oslo,” Jevanord explains. “And then some months later I was asked to come to London for a week in 1986. We started from scratch with ‘Cry Wolf’, using a drum machine on bass drum, snare and cowbell. Then I did all the cymbals and fills, using a full drum kit with lots of toms – my take took about 20 minutes to do, so the rest of the one-week session I was just present and watched! I remember that, after a couple of test takes, Paul told me to “go bananas”! And I did… that’s the take they used on the record!” On ‘Stay On These Roads’ (the title track), I just played some cymbals recorded at Rainbow Studio in Oslo. On ‘The Blood That Moves The Body’ I did the same as on ‘Cry Wolf’ the year before… not so good – more tame – but okay.”

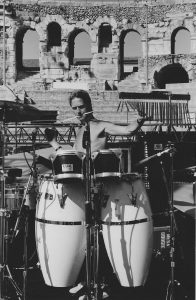

Jevanord was also a part of a-ha’s live band in 1987: “I was simply asked,” he says, when recalling his appointment. “And I said yes! An adventure – Mike Sturgis on drums and me on percussion; Ian Wherry on keys and Leif Karsten Johansen on bass. Seventeen concerts during three weeks in Japan, two concerts in Reykjavik, Iceland, and five outdoor concerts in the south of France, all during the summer of 1987.”

Erik Hagelien, the band’s original drummer, currently works for Hans H Schive (a battery manufacturer) and still sees Bondi occasionally: “Just for fun, our first band Essens were reunited about five years ago,” he says. “I meet Viggo and the others a couple of times a year, ending up with the same yearly performance at a local reunion party. I recently bought a second hand drum kit from a famous Norwegian drummer, Thor Andreassen. Viggo hated my digital drums and forced me to take this step which I am very happy for!”

As for Tore Aarnes, the owner of Octocon Studio, his first post-Fakkeltog project (and debut release on Octocon Records), was an impressive progressive rock album by Octopus, released in 1981. Titled Thærie Wiighen, and inspired by the writings of Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, this equally rare cult release featured Aarnes on keyboards and synths (a second album, Sica, remains unreleased). Other notable Octocon recordings included 1985 a-ha demos of ‘Scoundrel Days’ and ‘I’ve Been Losing You’; and ‘Dance With The World’, a synth-pop single by Aarnes (under the pseudonym Y Me) that Waaktaar had remixed.

Rebuilding Bridges

It was confirmed earlier this year that the Poem album is finally set for a long-awaited commercial release. “I’ve just mastered the second Bridges album,” Waaktaar tells me. “And I’m surprised how good it ended up sounding, considering the age of the tape and the modest studio we used.” In the meantime, fans can look forward to a brand new Savoy album (provisionally penciled in for September).

Fakkeltog is still a highly prized collector’s item, with some copies changing hands for over £500. It was unofficially re-released by Luna Nera Records as a limited edition in 2012, but the tracks are now easily accessible via vinyl rips on YouTube, giving a fresh generation of a-ha fans the opportunity to listen to this cult favourite. I asked Waaktaar about the master tapes and a potential official reissue. “Those tapes have worn a bit over the years,” he says. “I did get a transfer of the multi-track last year. And, who knows, maybe we’ll remix this one as well one day. The album was done on 8-track and the main performance is already mixed down on two tracks so it’s limited to what you can do to restore it.”

I asked Erik Hagelien, the band’s original drummer, what he thought about Fakkeltog. “Great album, with jazz rock elements,” he says. “My favourite is ‘May The Last Danse Be Mine’, since I knew this song so well from our playlist.”

“I think it’s good music,” adds Jevanord, fondly. “And we did what we could at the time to make it feel good. We were four happy, self-taught amateurs, but with good intentions in a cheap recording studio. I think it’s good if you think about that… and we made the album in one week!”

As for a Bridges reunion, Bondi recalled talk in the early 1990s of a potential reformation: “I was contacted by Paul and he said ‘I think we should talk about [getting] together again’… and I think Paul was thinking about Bridges actually at that stage… So I took out the old LP, was listening to the songs and started to practise and I was almost there, waiting for another phone call from Paul… still waiting for it!”

The Electricity Club gives its warmest thanks to Erik Hagelien, Øystein Jevanord, Paul Waaktaar-Savoy and Viggo Bondi

Thanks also to www.a-ha.com, a-ha-live.com, Jan Omdahl and Sara Page

Article and new interviews by Barry Page

All photos, courtesy of Erik Hagelien, Øystein Jevanord and Viggo Bondi

www.a-ha.com

www.facebook.com/officialaha/

www.waaktaar.com

www.facebook.com/waaktaarpal

www.magnef.org/

www.facebook.com/magnefuruholmen.official/

www.facebook.com/Dog-Age-9225271751/

- QUEEN’S MACHINES – How Music Changes Through The Years (1979 – 1984) - July 25, 2021

- SUGAR RUSH – The Story of ‘Sugar Tax’ - May 7, 2021

- Survival – The Story Of ‘Machine and Soul’ - April 30, 2021